It’s been a while since I went over the intricacies of the polar vortex/stratospheric warming events. The polar vortex has had more airtime over the last several years, and the term is latched onto when temperatures plunge well below normal in the winter months. This cold intrusion has been linked to stratospheric warming events.

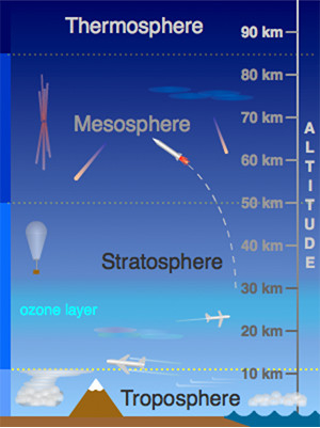

The stratosphere is roughly 10-50km into the atmosphere, the next sector of the atmosphere above the troposphere, which is where weather lies, as do we. The image, courtesy of UCAR shows four sections of the atmosphere – missing the Exosphere, which is above the Thermosphere (think infinity, and beyond!).

The troposphere and stratosphere are separated by the tropopause. This is the point at which temperatures warm with height, which is the opposite of what we typically see in the troposphere (unless we have inversions). While you can’t see the tropopause, you can occasionally get a visual from thunderstorm anvils in the summer. You’ll notice that at some point the cumulonimbus cloud no longer grows in height, and the clouds spread horizontally – that’s the tropopause (photo from a Farmington, ME thunderstorm).

Stratospheric warming is defined as a mass warming event in the stratosphere, increasing temperatures by some 50 degrees Celsius in a matter of days. Given that it’s incredibly high up in the atmosphere, we don’t feel that warming at the surface, but it has been linked to the opposite. We’ll generally see intense cooling in southern Canada and the United States about 30-60 days later.

Why does it happen? We have to go back to the polar vortex: “Vortex” refers to the counterclockwise winds (westerly) around the low pressure, and “Polar”, because we’re up in the poles. This permanent low pressure resides at our poles year-round, and this tight ring of arctic westerlies circles the North Pole. There’s a teleconnection, called the Arctic Oscillation (AO, for short) that is essentially a measure of the polar vortex’s strength.

The polar vortex doesn’t appear and reappear – you hear about it (and feel it) when it weakens, and the AO goes into a negative phase. When the ring of westerlies weakens, the vortex breaks down, and can even sometimes allow a change of direction (they become easterlies). This causes the cold air to descend quickly, which in turn causes a rapid warmup aloft – your “strat warm” event. As the cold air moves through the rest of the stratosphere and troposphere, it causes disruptions in the jet stream, which in turn causes a change in our weather pattern.

Typically we see cold, Canadian high pressures dominate the pattern a few weeks after stratospheric warming. Often this brings unseasonably cold air and even wintry weather to regions of the United States not used to such cold conditions.

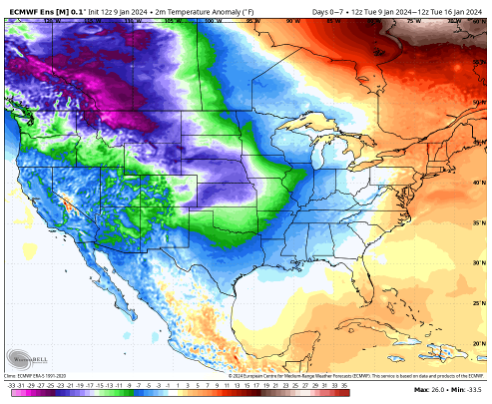

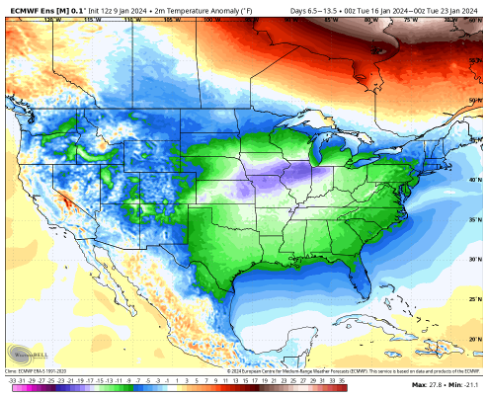

We had a stratospheric warming event in early December 2023, therefore it’s no surprise what we are seeing for the week ahead. The two images show 7-day surface temperature anomalies some 20-25 degrees below average into the Rockies and Heartland ending on January 16th. Those anomalies shift south and east the following week, affecting the Midwest, South, Southeast, and eventually the East.

This transitions nicely into our long term blog tomorrow!