On Thursday, Dec 5, we had a cold front come through New England that was forecast to drop temperatures during the day. As this was occurring, I started to notice something that had happened a couple times in the past – southern Vermont cooling faster than central and portions of northern Vermont.

With clients from Mount Snow to Jay Peak and data from all resorts, it helps time a cold front and just how far cold air has moved into a particular area. When I first started forecasting in the Green mountains, this was not what I expected. Why is Mount Snow colder than Stowe when the front moves from northwest to southeast? Given this throws off the timing of a forecast, I’ve started to monitor these for higher accuracy in forecasting frontal timing and temperature drops.

Here are summit readings from 12pm yesterday from south to north:

Hunter: 22°

Mount Snow: 22°

Stratton: 21°

Killington: 23°

Sugarbush: 22°

Mount Mansfield: 21° (so we can extrapolate Stowe’s summit at 22/23°)

Jay Peak’s summit station is down, but you can see the trend. While there are no major discrepancies here, you would expect a front coming in northwest to southeast to bring down the temperatures a couple of degrees before even getting to southern Vermont. And there’s elevation differences we’re leaving off the table as well.

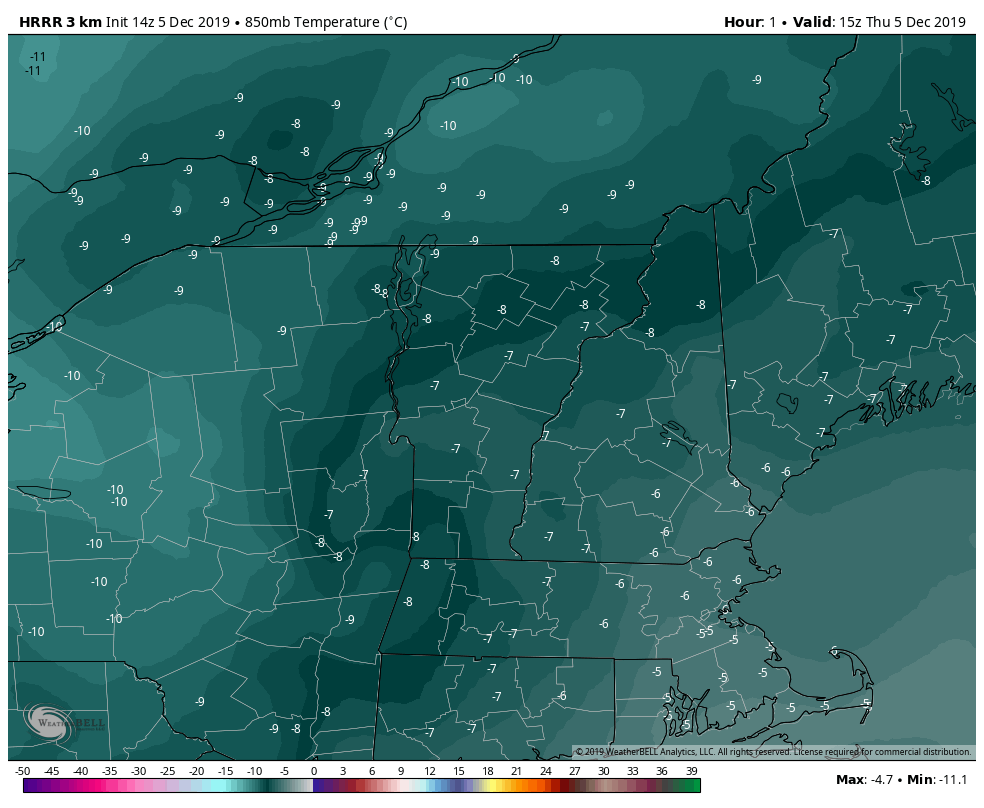

Our high resolution model, the HRRR, actually picked up on this in the 9am run of this rapid refresh model (image shown).

These are 850mb temperatures (~4,500 feet) valid at 10am on Thursday. You can see the hang up of the cold air in the Adirondacks (thanks Whiteface!), and instead of moving through Vermont, it’s streaming in north of Mount Mansfield, through northern New Hampshire (Wildcat summit 21° at 12pm) and Maine (Sugarloaf summit was also 21° at 12pm). But on the southern end, it circles up underneath the Adirondacks, and impacts Hunter, Stratton and Mount Snow, before impacting Killington, Sugarbush or Stowe. In the topographical map, it’s easy to see why it would take that path.

But why doesn’t it always take that path? Yesterday’s winds were not extraordinarily high. Summit winds were 20-35 mph, if that (Mansfield was only gusting to 20mph). When the winds aren’t very strong, the cold air doesn’t have enough power behind it to get up and over the highest mountain peaks. Therefore it finds the path of least resistance first – which is around the mountain summits.

Eventually the energy builds up enough against the higher summits (which likely causes an increase in wind – no data from Whiteface as the station is down from the fire, and Mansfield went down) – that the cold air does push and spill over, therefore by 6pm, temperatures looked a bit more “normal”.

Hunter: 19°

Mount Snow: 16°

Stratton: 16°

Killington: 14°

Sugarbush: 13°

Mount Mansfield: 13° (let’s say 14° Stowe top of the gondy)

This was the first time I’ve seen any model pick up on this, so I wanted to share with you as I figured you’d find it as interesting as I do. It was one frame of the 9am run of the HRRR, and by the 10am run, the model had smoothed it out. Forecasting in the Greens is humbling, and the nuances of the mountain forecasts are often missed by even the highest resolution models.